Monday, November 18, 2013

The Desert and the Real: Part 2

Here I continue, and finish, Part 2 of explanation of the ascetic life, which sprung from the story of Fr. Maxime. Part 1 is HERE.

CONTEMPLATION

Having been driven to the desert, the choice to go there is, itself, a renunciation of the lesser reality of material things. The favor for spiritual things over material things is affirmed in a life defined by a constant habitual rhythm of contemplative prayer. It is spiritual things that are contemplated in contemplative prayer, of course. The willful poverty (part of the monastic vows) and ascetic lifestyle of the monk, particularly one in solitude in the wilderness, is a practical extension of that analogical choice to listen to the Voice that drives a man into the desert. Do note that, in the short video of the chanting from Abbaye du Thoronet (there was a link to this video at the end of Part 1), you can’t see from where the voice is coming.

“…the ‘unreality’ of material things is only relative to the greater reality of spiritual things…When we let go of [material things] we begin to appreciate them as they really are. Only then can we begin to see God in them. Not until we find Him in them, can we start on the road of dark contemplation at whose end we shall be able to find them in Him.” - from Thomas Merton's Thoughts in Solitude

*Note: from here on out, all quotes will be from Merton’s Thoughts in Solitude, unless otherwise noted. Thomas Merton, by the way, was a Trappist monk in Kentucky in the mid to late 1900’s.

Historically, the prayer life of the ascetic, which Merton refers to as “dark contemplation,” is bathed in this idea of renunciation of sensory, created reality. The “darkness” of contemplative prayer is not intended to be the “darkness” through which the worldly wander. The “darkness” of contemplation for the ascetic is associated with the awe, wonder, and mystery of the cloud that surrounded Elijah when he fled to the desert after confronting Jezebel. This is the same cloud that descended upon the completed Temple in Jerusalem. The idea of contemplative prayer is to see the face of God, to have an encounter with the Uncreated. In this sense, the “darkness” of contemplation is the pillar of fire by which Israel made it’s way through the desert.

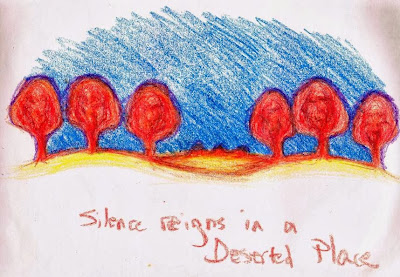

The image depicted above is a crayon coloring I did as I traveled through the desert on the way from Bilbao to Barcelona, Spain while studying abroad in my fourth year of architecture school. I had much of the idea of this blog post in mind as I did that drawing. What Merton refers to as renunciation of sense and visibility very strongly corresponds to what I meant by “Silence” in the title or caption. Just as the darkness of contemplation is not the absence of light, Silence is not the absence of sound. Silence is penitent quieting of the self, heard in the spirit of the monk’s vows in the first place and seen in the image of the dry barrenness of the desert bathed in sunlight and grace.

“The LORD said, ‘Go out and stand on the mountain in the presence of the LORD, for the LORD is about to pass by.’

Then a great and powerful wind tore the mountains apart and shattered the rocks before the LORD, but the LORD was not in the wind. After the wind there was an earthquake, but the LORD was not in the earthquake. After the earthquake came a fire, but the LORD was not in the fire. And after the fire came a gentle whisper. When Elijah heard it, he pulled his cloak over his face and went out and stood at the mouth of the cave.” – 1 Kings 19: 11-13

EDIFICATION

“Detachment is not insensibility…If we are without human feelings we cannot love God in the way in which we are meant to love Him – as men….The control of emotion by self-denial tends to mature and perfect our human sensibility. Ascetic discipline does not spare our sensibility…We must suffer. But the attack of mortification upon sense, sensibility, imagination, judgment and will is intended to enrich and purify them all. Our five senses are dulled by inordinate pleasure. Penance makes them keen, gives them back their natural vitality, and more. Penance clears the eye of conscience and of reason. It helps us think clearly, judge sanely. It strengthens the actions of our will. And Penance tones up the quality of our emotion…We must return from the desert like Jesus or St. John, with our capacity for feeling expanded and deepened, strengthened against the appeals of falsity, warned against temptation, great, noble, and pure.”

Again, the mad thirst of the desert forces a choice upon us. Because the desert is so explicitly a picture of what is not there, going to the desert is a completion (perfection) of our Christian walk. The desert becomes a picture of that for which the ascetic is truly grateful. The Christian is not grateful in the desert for worldly things, the things enjoyed by the Saducee within.

“To be grateful is to recognize the Love of God in everything He has given us – and He has given us everything. Every breath we draw is a gift of His love, every moment of existence is a grace, for it brings with it immense graces from Him. Gratitude therefore takes nothing for granted, is never unresponsive, is constantly awakening to new wonder and to praise of the goodness of God.”

VIRTUE

“The grace of God, through Christ Our Lord, produces in us a desire for virtue which is an anticipated experience of that virtue. He makes us capable of ‘liking’ virtue before we fully possess it. Grace, which is charity, contains in itself all virtues in a hidden and potential manner, like the leaves of the branches of the oak hidden in the meat of an acorn…Habitual grace brings with it all the Christian virtues in their seed. Actual grace moves us to actualize these hidden powers and to realize what they mean: - Christ acting in us.”

The ascetic life is conceptually shaped by contemplation, by not doing anything (in every sense of the phrase “not doing anything.”). But for the desert fathers, renunciation of sense serves a bigger but rather pragmatic end: to, through penance, overcome despair and defeat and become more like Christ. Contemplation does not serve a purely intellectual end. Life in the desert is meant to be the fruition of virtue.

“Laziness and cowardice are two of the greatest enemies of the spiritual life…sooner or later, if we follow Christ we have to risk everything in order to gain everything. We have to gamble on the invisible and risk all that we can see and taste and feel. But we know the risk is worth it, because there is nothing more insecure than the transient world. ‘For this world as we see it is passing away’…Without courage we can never attain to true simplicity. Cowardice keeps us ‘double minded’ – hesitating between the world and God. In this hesitation, there is no true faith – faith remains and opinion.

“There is no neutrality between gratitude and ingratitude…if we do not love Him we show that we do not know Him. He is love…Our knowledge is perfected by gratitude…A man who truly responds to the goodness of God, and acknowledges all that he has received, cannot possibly be a half-hearted Christian. True gratitude and hypocrisy cannot exist together.”

HOPE

“We are never certain, because we never quite give in to the authority of an invisible God. This hesitation is the death of hope. We never let go of those visible supports which, we well know, must one day surely fail us. And this hesitation makes true prayer impossible…”

We are driven to the desert, but the thirst found in the desert forces us to make a choice as to how we will quench it. We go to the desert to see what lies there, or we go to become the desert. The seed of our heart can remain closed, or the choice to go to the desert can be the seed splitting open to make room for the shoot to rise to life. Contemplative Silence is the barrenness of the desert. The monk doesn’t hear Silence; he becomes quiet. This is the death of the self. “Unless a seed falls to the ground and dies…”

“If we know how great is the love of Jesus for us we will never be afraid to go to Him in all our poverty, all our weakness, all our spiritual wretchedness and infirmity. Indeed, when we understand the true nature of His love for us, we will prefer to come to Him poor and helpless. We will never be ashamed of our distress. Distress is to our advantage when we have nothing to seek but mercy…The surest sign that we have received a spiritual understanding of God’s love for us is in the appreciation of our own poverty in the light of His infinite mercy.”

Being bathed in the barrenness of the desert is a becoming of a self-portrait. By that, I mean to say that the desert becomes a self-portrait. The ascetic becomes what he sees of himself in the poverty of the desert. Need for God is part of what drives him there in the first place.

“Hope is the secret of true asceticism. It denies our own judgments and desires and rejects the world in its present state, not because either we or the world are evil, but because we are not in a condition to make the best of our own or the world’s goodness. But we rejoice in hope. We enjoy created things in hope. We enjoy them not as they are in themselves but as they are in Christ – full of promise. For the goodness of all things is a witness to the goodness of God and His goodness is a guarantee of His fidelity to His promises. He has promised us a new heaven and a new earth, a risen life in Christ. All self-denial that is not entirely suspended from His promise is something less than Christian.”

The desert becomes a reminder of God’s promise. The fullness of hope is present in the dry wasteland. When the ascetic closes his eyes in contemplative prayer, the fleeing from this world and the renunciation of sense becomes an expression of the not yet. In faith, he opens his eyes to heavenly virtue. The desert becomes a picture of this opening, and the opening occurs in the desert. Life in the desert, then, becomes a picture of life as a pilgrim in tents blowing in the wind of the Spirit.

“My Lord, I have no hope but in Your Cross. You, by your humility, and sufferings and death, have delivered me from all vain hope. You have killed the vanity of the present life in Yourself, and have given me all that is eternal in rising from the dead…Why should I cherish in my heart a hope that devours me – the hope for prefect happiness in this life – when such hope, doomed to frustration, is nothing but despair? My hope is in what the eye has never seen. Therefore, let me not trust in visible rewards…Let my trust be in Your mercy, not in myself. Let my hope be in Your love, not in health, or strength, or ability or human resources. If I trust You, everything else will become, for me, strength, health, and support. Everything will bring me to heaven. If I do not trust You, everything will be my destruction.”

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]